by Gina Malczewski

Women’s history is often one of quiet change—while protests and resistance of various types gained necessary attention and forced discussion, those who followed the rules and demonstrated their competence also had their impact.

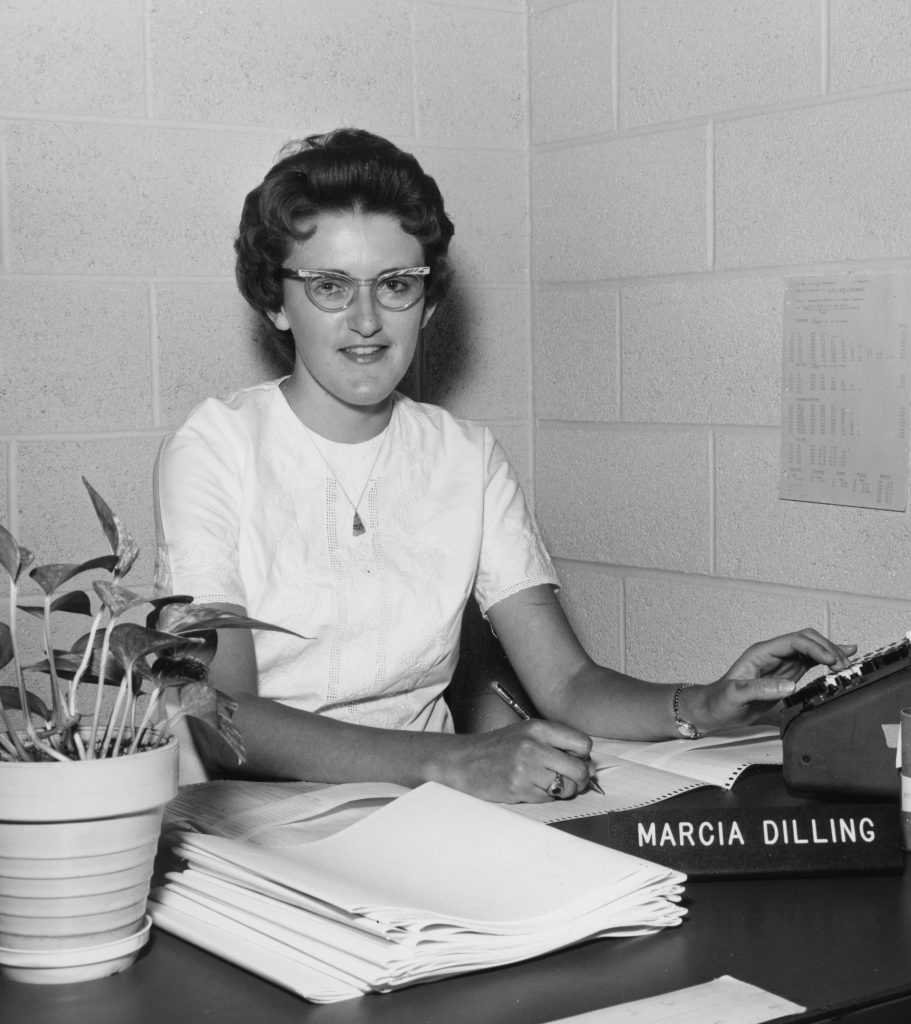

Marcia Dilling and her husband Wendell are important members of the Midland Community and active in many different ways– and both have left their mark on the Midland ACS. Marcia used her skills for the Society mostly during her years as newsletter co-editor, Section historian and Board member. Wendell’s volunteerism has spanned decades and he is still serving on the Board of Directors and as Section Historian. The following attempts to tell Marcia’s story and remind young women and others in chemistry how far we have come.

Marcia Dilling was raised in northern Illinois. “I grew up in a small rural community…and was not acquainted with any scientists, but my mother, who graduated from high school in 1931, talked about how much she enjoyed her chemistry class. This inspired me to take all the high school science classes I could — elementary biology, physics, chemistry. Mother put me in touch with a chemist she knew who worked for DuPont in Delaware. I interviewed him through an exchange of letters. He said his reason for going into chemistry was because he liked to see solutions turn from one color to another. I could relate to that.”

When Marcia left for college, like so many other women in the past, she was encouraged to become a teacher. (English was suggested in her case.) She chose a different path and majored in chemistry. Her small institution (Manchester College), had interesting rules for women: “[we] had a 10pm curfew Sunday-Thursday and 11pm Friday-Saturday, unless special permission was obtained from our elderly house mother. Men had no curfew. Women could wear slacks only on Friday. I can’t imagine the reasoning behind this…” Marcia met Wendell at Manchester where he was a lab assistant. They married and enrolled at Purdue, where he attended graduate school and she finished her BS while working as a lab technician.

In 1962, Marcia and Wendell joined Dow; she interpreted mass spectra collected with Dow-made instruments—only union personnel were allowed to operate the instruments and obtain the spectra. “We did sometimes get to separate mixtures using prep column gas chromatography (GC),” she recounts. [It is notable that the combination of GC and mass spectroscopy was invented at Dow by Fred McLafferty and Roland Gohlke and is considered an analytical breakthrough; Midland Dow was designated an ACS National Historical Chemical Landmark for this invention.] “I analyzed the spectra to (hopefully) determine the structure of organic molecules synthesized by chemists at Dow and wrote brief reports summarizing my findings. Sometimes the results I reported were incorporated by research or production employees into Company reports called CRI Reports…”

At Dow, women also had gender-specific experiences. “Shortly after hiring into Dow, I was given a written standardized psychological test and then had to listen to the company psychologist discuss the results. I remember he told me it appeared I hadn’t been completely truthful… Apparently he found some inconsistencies in my answers. He also asked when I planned to have children and how many.” Marcia mentioned that the test was multiple choice, and sometimes none of the options reflected her preferred answer, which may have led to inconsistencies in the results. Her husband doesn’t remember being required to take the test.

“Women also had to wear skirts to work, no slacks allowed, not even during one cold winter when a boiler at the power plant exploded, resulting in very low temperatures in our building. Most of us wore our winter coats while working. One woman actually dared to wear slacks under her skirt. I expected her to be fired at any minute. I had to go to the chlorine plant one time and climb see-through stairs to the second floor. That was embarrassing, as there were men working on the first floor.”

She continues: “At Dow in the 1960’s, women were not permitted to drive inside the plant. The building I worked in (#1603) was across the street from the plant. (It’s now inside the plant fence.) If I needed to go to a building inside the fence, I had to get a man to drive me there, or take a plant bus. Riding the bus was actually kind of fun; Wendell and I used to ride the bus all over the plant during our lunch hour.”

Marcia left to have their daughter in 1967—at the time, Dow required women to quit five months into their pregnancies, and time off for successive children was not a foregone conclusion. “Maternity leave was rare, and not much child care was available anyway, “she says. “I returned to work for Dow part-time, at home, in the fall of 1969, indexing technical progress reports to produce a keyword-in-context (KWIC) manual index used by researchers to find information about work previously done at Dow.” She was grateful for the at-home work but missed having personal interactions with other technical people.

Marcia worked up from one-quarter time to full time, and returned to the Dow Campus. At her supervisor’s request, she also did literature searches for a salt company in OH using “dusty old Chemical Abstracts Service volumes in 566 building, some dating back into to early 1900’s.”

“In a the late 1970’s, I was assigned an office in CRI in 566 building,” Marcia continues. “I learned chemical nomenclature from fellow employee Stan Klesney, an international expert on the subject, and formulated chemical names according to Chemical Abstract Service rules, when asked to do so by Dow researchers and for inclusion in Dow reports. I also looked up CAS numbers for compounds upon request. Early on this was done manually using printed CAS volumes, prior to CAS’s development of an online database. I also assumed responsibility for overseeing updates to Dow’s CRI reports system and chemical registry, two separate collections of data that were being converted from manual card files to online systems. Keypunchers and typists entered data from the cards into a file that was batch processed into the main databases. Originally the file cards were stored in a building inside the plant, and they still retained a faint odor, not unpleasant, from those previous days.”

Marcia’s attention to detail and communication skills also were put to use for technical writing and editing. At one point, she was also supervising 11 employees. “I edited a newsletter for several years that was distributed to researchers. I also wrote procedures and quick-reference guides for using department databases,” she says.

Marcia’s career parallels the changes that were occurring in society. As she recalls, “By the time I stopped working at home for Dow and returned to the company, wearing slacks was allowed and women were permitted to drive inside the plant.” She participated in the evolution of chemical record computerization, and the fact that so many of her skills were utilized in various aspects of her career reflects both her flexibility and that of supervisors who were doing more to realize and accept the value of each individual. She retired in 1995.

Marcia and Wendell became co-editors of The Midland Chemist, the ACS monthly newsletter, in 1969, at the request of editor Joe Dunbar, who initiated the publication in 1964. At that time The Midland Chemist was put together totally on paper and the mockup was taken to Pendell Printing and made into booklets that were mailed to each member. (More than 30 years passed before the publication went digital.) The couple performed this service until 1973.

“In retirement I quickly developed other interests, “ Marcia states, “including volunteering for several nonprofit organizations and spending more time with friends.” Marcia is currently an active photographer, enjoying both the documentation and artistic aspects of this pursuit that she first saw her father practice many years ago.

In the previous century, although they usually followed the rules, Marcia and other women like her have been role models and trailblazers in many sometimes quiet ways, demonstrating proficiency and providing evidence that women could be multi-taskers and accomplished professionals – in chemistry and other once all-male fields.